The quest for the holy grail.

02 May 2023For those of us not acquainted with Arthurian legend, the holy grail–according to Merriam-Webster–can be “an object or goal that is sought after for its great significance”.

With respect to software engineering skills, the quest for the holy grail can be embodied in the pursuit to become a full-stack developer.

A full-stack developer is one who is capable of producing both the front-end and back-end of an application.

The front-end refers to that part of the app that the user would see and interact with, and is interchangeably referred to as the “client-side” in a website context.

The back-end refers to the parts that the user doesn’t see, and is interchangeably referred to as the “server-side”.

A developer can specialize in either, and it seems that many pursue at least a cursory understanding of both, but each person inevitably tends toward either one of them according to their strength or experience.

The holy grail

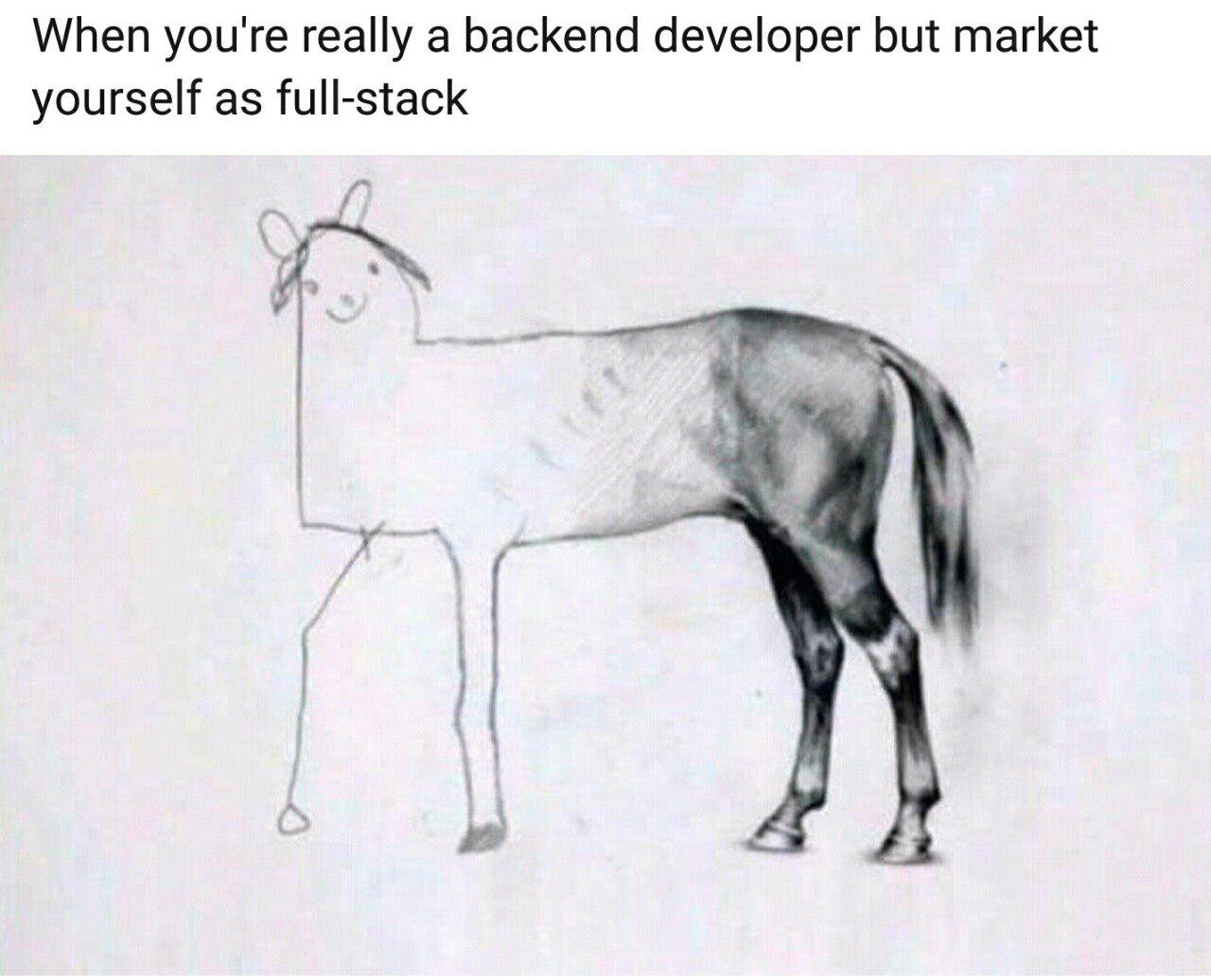

The holy grail more resembles a utopian ideal in the context I framed for it–though it is possible to truly know both intimately–and can distort the reality into something comical, illustrated hilariously by this meme.

In my opinion, though, the ability to have something simple at the front is preferable to leaving it blank, even if it is wrong, as long as it works to tentatively complete the picture.

Therefor the quest goes on, and the following is my current understanding of the tools I’ve learned to use in this pursuit; the brushes and paint and canvas of our art through webpages.

Framing the conversation

The function and purpose is significant when choosing a Language and Run-Time Environment (RTE) to write the program for.

The RTE acts as the interpreter between your program and the different pieces of the hardware your program runs on or uses–like the hard-drive, processors, or screen–and have varying strengths and weaknesses.

The environment I’ll be talking about here will be Node.js, and the Javascript language.

Having an RTE is sufficient to create simple programs, especially when they don’t interact with a person, but it often is the case that we want that interaction and require a higher standard level of complexity.

We can start off a little farther ahead, rather than creating everything from scratch, by using frameworks.

Frameworks are sets of pre-made tools and resources that serve as the backbone, or frame, of either the front or back end of an application.

Frameworks come in Packages that we can include in Node.js by installing them directly from the internet through the Node Package Manager (NPM) as they’re needed.

Choosing the right tools for the job

Frameworks are classified based on which part of the application it is relevant to; so there are front-end frameworks and back-end frameworks.

Front-end frameworks

An example of a front-end framework is React which fully integrates normal javascript with HTML and CSS, which is somewhat more involved to accomplish otherwise, into objects called Components.

Another example is Bootstrap which provides commonly used combinations of HTML and CSS for the layout and theming of webpages through easily referenced objects called Classes.

Back-end Frameworks

An example of a back-end framework is MongoDB that implements the design pattern–the most efficient generic shape that a commonly desired functionality takes–of storage and security for data.

The package allows a program to protect its data from users by segregating them from the server and forcing them to interact with client clones of the databases.

Other packages

Some frameworks come as combinations of packages that are often used together, as for React-Bootstrap.

Packages can even expand frameworks, like the Uniforms-bootstrap5 package, which satisfies the common need of many React-Bootstrap apps to retrieve information from forms–the placed where users give input, like email and password for signing in–on webpages and ensuring that the data is valid.

Their powers combined

A third type of framework correlates to the combination of both the front and back ends and is intuitively referred to as a full-stack framework.

A powerful example of this is called Meteor which combines MongoDB with different front-end frameworks, including React-Bootstrap through Node.js and NPM.

To whom it may concern

Whether when writing the same “Happy New Years, Person-Y!” or reprinting job resumes we see boilerplate all the time.

The boilerplate is the repetitive parts of a document and are then naturally produced into a generic form that we can re-use called templates.

Templates for Meteor-React include all of the necessary packages that it commonly takes to make those specific types of webpage-applications function.

The ones I’ve been using included helpful working examples of databases and webpages with basic page navigation and user accounts already implemented.

Forming a party for the quest

The best part of having a full-stack framework is having a single folder to work in, especially for when a team of people are contributing to different or both “ends” of the program’s files.

Common access to that folder is the obvious first problem but can be solved by storing the folder in a central accessible location, like github.

Further easily-foreseeable problems can include a clear understanding of the tasks needed to be done to complete the work, and a common vision for the end product.

Issue-Driven Project Management solves this problem by having a central location for planning, separate from the actual content of the project, where team members create and manage a list of issues.

Issues are tasks–or groups of tasks–that take an approximately equal amount of time to complete, preferably 2-3 days, but can be adjusted to encompass more or less based on how much work it turns out to actually take to complete them.

Projects can have groups of issues called Milestones which can represent certain phases of development like planning, implementing, and testing.

Team work makes the dream work

Our endeavor for the holy grail should ideally lead to an understanding of both ends of development as much as possible.

The reality, however, is that it is much more efficient to work as a group with those whose strengths complement your own.

In this way the quest for the holy grail can be brought to a success much sooner in the form of the collective.